Italy’s Insurance Regulator IVASS has recently conducted a study into the country’s unit-linked policies and other insurance-based investment products which was aimed at intercepting possible cases of greenwashing in the industry.

The study has assessed sustainability claims of over 100 domestic policies, related to over 1 million contracts and approximately €50bn of insurance premia. You can read the full report here.

While the IVASS analysis did not reveal any obvious cases of greenwashing, it also highlighted the substantial absence in the domestic insurance market of so-called “dark green” products, i.e.policies that include sustainable investments as an objective of the investment policy (Article 9 products as per the EU’s SFDR).

About 92% of products are instead classified as “light green”, that is Art. 8 products that promote, among others, environmental or social characteristics in investment policies, while the remaining 8% are not even “light green” but just Article 6 products which only include sustainability risks in investment choices.

Interestingly, the study has perceived a degree of caution by asset managers when classifying the products as as as “light green“, “dark green” or Article 6, reflecting the possibility of “bleach-washing” (that is, when asset managers prefer not to define a financial product as more or less sustainable in order to reduce disclosure obligations and avoid legal risks).

Niche Asset Management manages two Article 9 SFDR funds, which as well as being 100% sustainable are also thematic, global and managed with a deep value investment approach: the Electric Mobility Value Niche, a high-growth theme fund, trading at deep-value multiples and managed by the team that in 2015 launched the world’s 1st electric mobility fund ever; and NEF Global Ethical Trends, a global ex China fund with about 275 stocks spread across 27 thematic portfolios functional to the achievement of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

Our deep value approach, which guarantees extremely low turnover, enables continuous engagement between Niche AM and the management of companies in the portfolio, thus allowing careful monitoring of corporate sustainability policies.

We do not do purely formal screening-offs or tick-the-box analyses. No green-washing, and certainly no bleach-washing.

For details on both funds see here.

This is a marketing communication for institutional investors. Please refer to Fund Prospectuses & KIDs before making any investment decision.

For any questions email us on: info@nicheam.com

Follow us on LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/niche-am

Back Read More

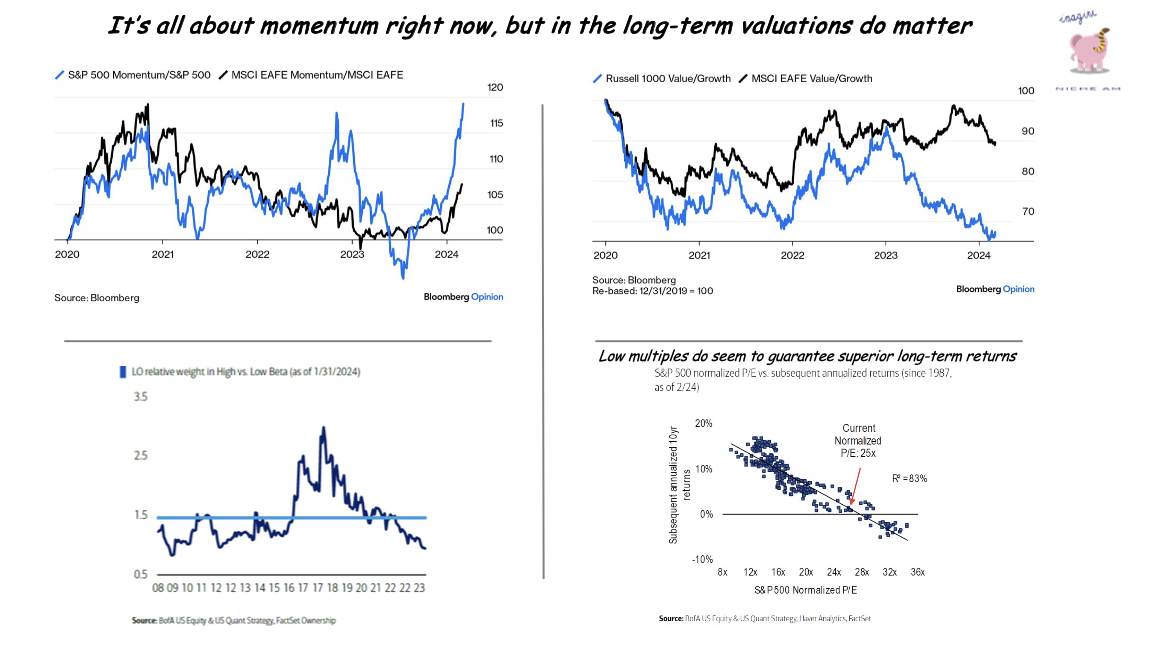

Are stocks in a bubble which may be about to pop?

Who knows.

There certainly seems to be a degree of irrational exuberance in some pockets of the equity market, but as Keynes has famously observed markets can stay irrational for longer than one can stay solvent. Most importantly, the variables we need to know to solve the bubble equation (inflation, interest rates, liquidity, productivity, geopolitics, etc) are too many and mostly imponderable.

However, while we can’t predict we can certainly be prepared.

And the way to be prepared is and has always been to hold a properly diversified portfolio – in terms of investment style, industry, market cap size, number of holdings and geographical and currency exposure.

Investors are currently overexposed to seemingly expensive and overcrowded momentum strategies, paying arguably excessive premia for a very small fraction of mainly big-cap stocks within über-concentrated portfolios.

Niche AM funds provide investors with a much-needed, prudent counterbalance, through highly liquid and diversified portfolios of value stocks, many of which are found among neglected sectors and overlooked geographies.

Value stocks have rarely been as cheap and as attractive in terms of financial strength, earnings prospects and sector breadth as today. The style should benefit going forward from the boost to global economic growth which could come from two likely and massive secular trends, i.e. energy transition and deglobalisation.

True, valuation has seldom been a strong predictor of short-term stock performance (as the near term is often dominated by the “noise” of news-flow, fads and emotions), but it seems to be a strong predictor for the longer-term, explaining on some estimates about 80% of 10-year stock returns.

While history doesn’t repeat itself, it does often rhyme and perhaps it is worth remembering that in the 10 years after the burst of the 2000 tech-bubble, value strategies have significantly outperformed.

To sum up, and paraphrasing Buffett, you can’t predict a bubble or a bubble bursting, but you can make sure you are not caught swimming naked when the tide goes out.

This is a marketing communication for institutional investors. Please refer to Fund Prospectuses & KIDs before making any investment decision.

For any questions email us on: info@nicheam.com

Follow us on LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/niche-am

Back Read More

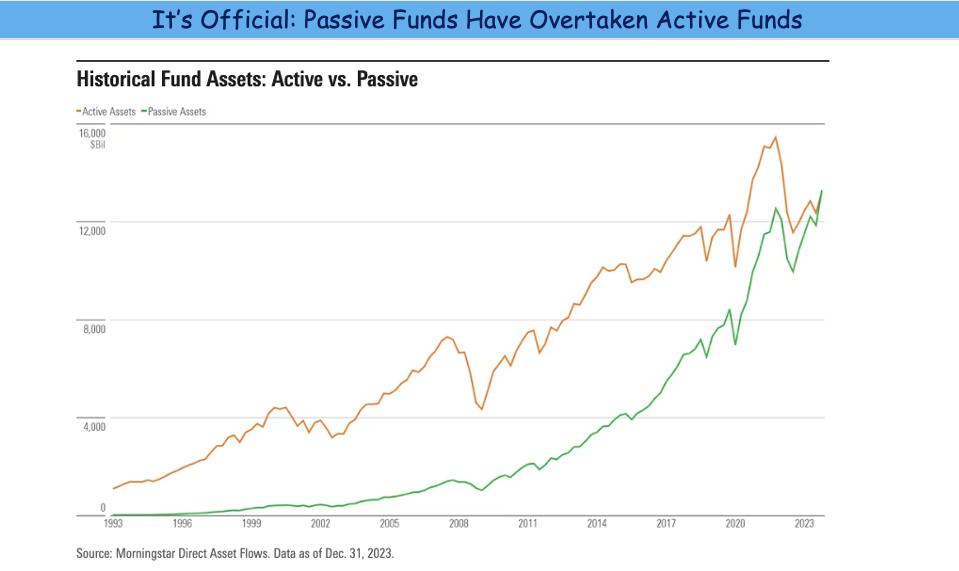

Has passive investment broken value investing, as argued by Greenlight Capital’s Einhorn? See here.

The logic is clear. By throwing in a wall of money onto stocks, or withdrawing that wall, no matter the valuation or fundamental strength of the underlying company, index investing undermines the signalling function of market prices for the allocation of capital and along with that the efficacy of value investing.

Passive investors – Einhorn’s argument goes on – have no opinion about value, which means that “when money is moved from active to passive, value managers get redeemed, value stocks

go down, it causes more redemptions of value managers, it causes those stocks to go down more and so on”. The conclusion sounds somewhat apocalyptic: “the value industry has gotten completely annihilated”.

There is certainly some truth in this argument, but paraphrasing Mark Twain, reports of our death are greatly exaggerated.

Passive investing in the US, the world’s biggest market, is (for now) only ~50% of institutional equity funds, which means that the remaining US$14.3 trillion of active investing is reasonably

more than enough for the price discovery mechanism to continue functioning. In fact, just a small share of fundamental, active investing would probably do the job.

In general, there is ample evidence that passive and active value strategies complement each other, with passive being often the core of a portfolio and active value a portion allocated for

potential outperformance, thematic exposure and risk mitigation. Today, value investing provides a much-needed counterbalance to passive investing and to investor euphoria about technology stocks.

This is a marketing communication for institutional investors. Please refer to Fund Prospectuses & KIDs before making any investment decision.

For any questions email us on: info@nicheam.com

Follow us on LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/niche-am

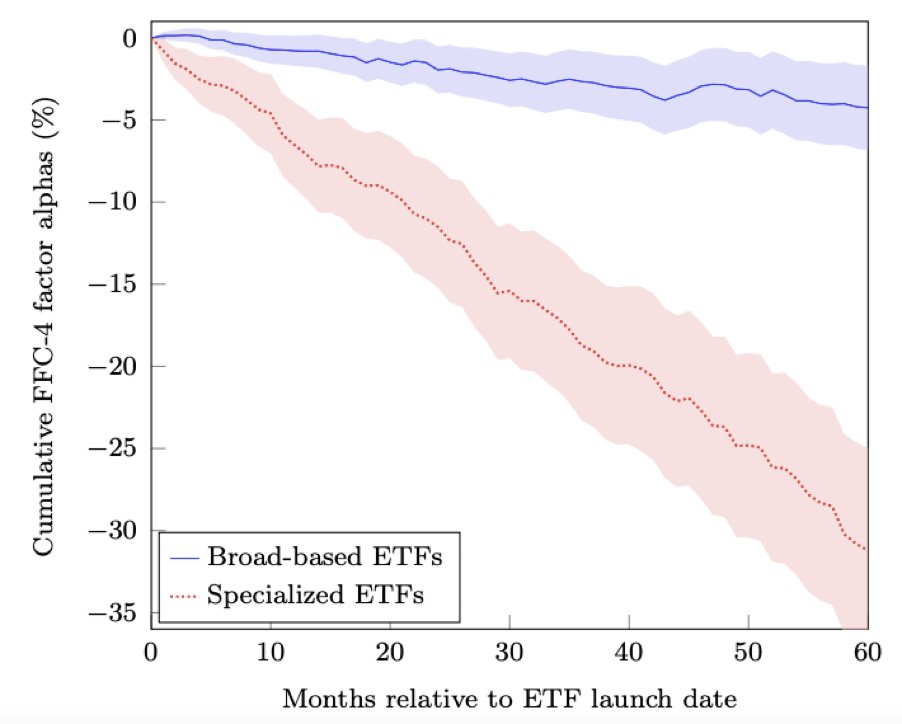

Read MoreDoes thematic investing create value for investors?

Not quite, according to this NBER paper which shows that at least in the ETF space, thematic investments underperform broader funds by about a third over the five years after launch, delivering negative alpha of about -4% a year.

The argument is not new: thematic ETFs are generally launched just after the very peak of excitement around an investment theme, holding portfolios of “hot” assets already overvalued at

launch and with über-high expectations. As industry and media hype vanish or financials disappoint, thematic investment underperforms or delivers negative risk-adjusted returns.

We couldn’t agree more.

That’s why at Niche AM we don’t really invest in themes but rather in niches, i.e. assets or themes which are all but neglected by the market and are thus deeply undervalued and entirely off-radar for investors and media.

Niche AM’s mission is somehow to find a theme before it becomes so. The niche may take time to attract investors and deliver potentially strong returns, but the enormous valuation opportunity makes it worth the wait.

This is a marketing communication for institutional investors. Please refer to Fund Prospectuses & KIDs before making any investment decision.

For any questions email us on: info@nicheam.com

Follow us on LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/niche-am

Back Read More

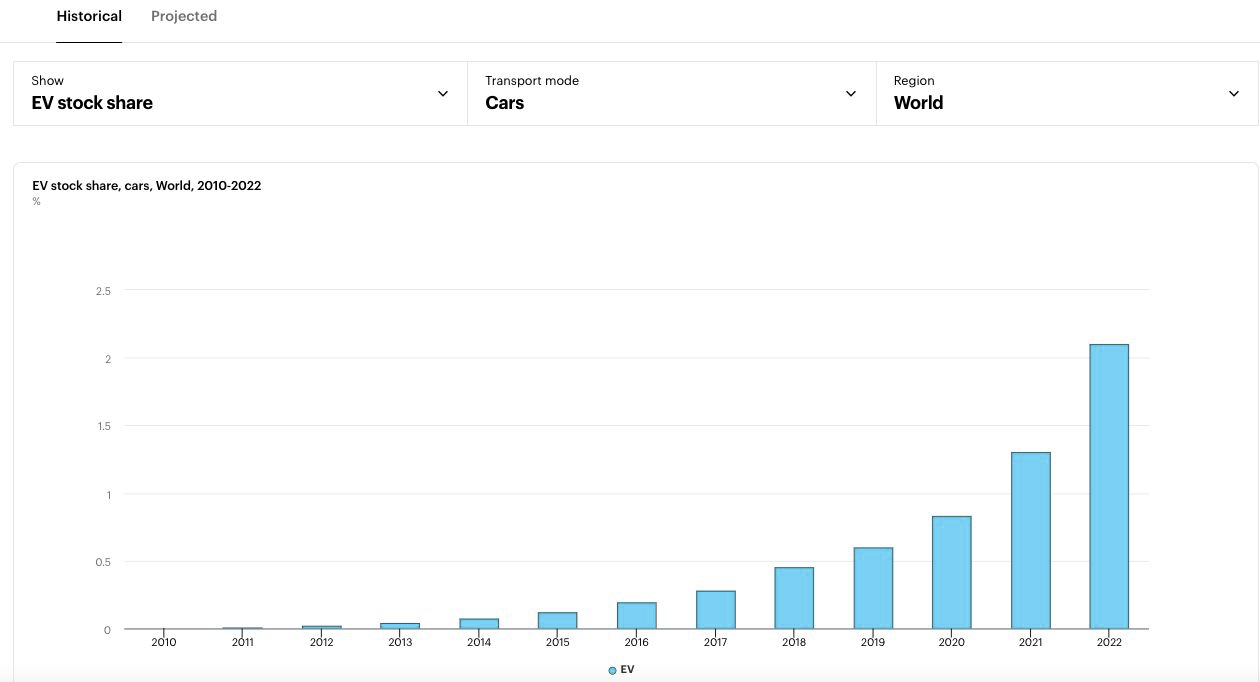

Electric mobility funds have fared poorly since the middle of last year mainly on concerns about China flooding the market with cheap EVs, with some ETFs declining by as much as 30%-35% since July.

This looks overdone, partly the result of the pendulum in investor sentiment between euphoria and pessimism.

The future of the world remains squarely electric, with the electric mobility megatrend here to stay, supported by environmental concerns, government incentives, technological progress (making EVs more affordable and better performing), infrastructure development and favourable consumer preferences.

Global market-sales share for electric vehicles is growing fast but remains at an average of ~15%, while global market-penetration is still on average ~2.0% (source: IEA).

In other words, e-mobility has not even embarked on the fast-growth and fast-adoption stage of the S-shaped penetration curve but some investors have seemingly already given up.

Paraphrasing MIT’s Malone, every technology breakthrough takes twice long as expected but half as long as the industry and the market are prepared for. And what the market is not yet prepared for and therefore not yet pricing in e-mobility stocks is the under-capacity scenario we still expect for the battery space, which should give key battery players stronger pricing power, better margins/earnings and higher valuations.

Yet not all that shines is gold….and not all e-mobility funds are equally attractive or equally effective in generating returns while protecting capital across cycles.

Our Electric Mobility Value Niche is a global equity fund that offers exposure to the EV battery ecosystem, investing in electric mobility players not recognized as such by the market and thus with potential for significant re-rating. The battery ecosystem represents 75% of the portfolio.

The chart below shows performance since inception for Niche AM’s E-mobility Value Niche fund vs ETF peers BATT and LIT. Yes, the latter has generated slightly higher returns over the period, but it has achieved so with double the volatility and a drawdown 3.5x as high.

At Niche AM we believe investment is as much about generating returns as about controlling risk, which we do by:

1. adopting a deep-value approach, as the price paid for the asset is the main determinant of its downside risk – this approach eliminates the risk of investing into a bubble

2. avoiding leverage at companies held in the portfolio

3. building a highly diversified portfolio

4. implementing an ESG-responsible approach, which reduces regulatory and political risk.

Within this framework market-timing, always challenging if not impossible, becomes less warranted.

For details on our EMVN fund see here.

This is a marketing communication for institutional investors. Please refer to Fund Prospectuses & KIDs before making any investment decision.

For any questions email us on: info@nicheam.com

Follow us on LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/niche-am

Back Read More

Will value stocks outperform growth in 2024? No one can know. Paraphrasing Galbraith, the only function of market forecasts is to make astrology look respectable.

Stock prices are the result of the aggregated activity or decisions of billions of producers, consumers, workers, investors and savers across the world influenced by forces which are sometimes known in advance but most often unknown and random.

Within a time-horizon as short as 12 months anything could happen and market-timing stocks or investment styles would just be speculation, not investing. Diversification and a well-balanced portfolio of both value and growth stocks remain the best long-term strategy for investors.

That said, what is the investment case for a rotation out of growth into value stocks? There are several drivers, some of which the result of possibly new structural trends.

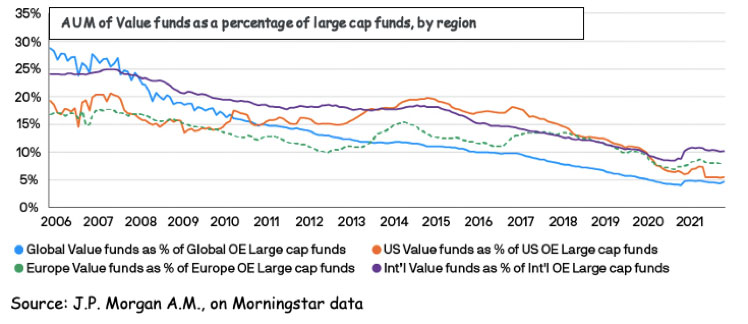

Both investor positioning and valuation spreads are too extreme.Partly forced upon investors by the composition of major stock indices, the proportion of value funds over total equity funds has fallen to as low as 5%-10% from the 20%-25% of the years before the Great Financial Crisis. Valuation spreads between value and growth stocks remain near historical highs, even higher than at the zenith of the TMT bubble. This look unsustainable if mean reversion is to maintain a minimum of credibility as investment tool, or even only for diversification and risk mitigation.

Back Read More

As the Nikkei 225 continues to hit new highs, the question for many investors seems to be: is this it, is the rally done?

We think Japan’s equity market remains a trove of quality, competitive, high-earning and undervalued companies, which is now benefitting from an accelerating wave of reforms in corporate governance and financial regulation.

Despite the recent rally, Japanese equities remain below 1989 levels. Market valuations are still attractive: ~1/3 of listed companies have 40% more cash than their market capitalisation while ~45% trade at less than 1x tangible net assets and ~60% are debt-free.

Recent updates to the corporate governance code, which pressure listed companies to offload their large equity cross-holdings, could result in ever increasing M&A and MBO activity as controlling shareholders try to fend off the risk of shareholder activism.

Further support could come from the ripple effects of the introduction last year of the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s 1x Price-to-Book rule, which requests listed companies trading below book value to explain their action plans to generate returns above the cost of capital and close the valuation gap. This should help drive greater management focus on shareholder value and further accelerate the pace of buybacks.

Retail inflows into equities could also increase after last year’s revision to Japan’s tax-free individual investment accounts, which is aimed at freeing ~€12.6 trillion in household financial assets mostly held in cash deposits.

Geopolitics should also help: Japan is increasingly seen as a play on China’s possible economic recovery without its geopolitical and domestic policy risks.

An uncontrolled Yen appreciation as a result of higher interest rates could have an impact on Japan’s equity market (mainly via negative effects on exporters) but it is also conceivable that at least a part of the funds which would repatriate following the break of the carry trade could find their way into domestic equities.

By focusing on companies not covered by the sell-side, our Orphan Companies project invests in a market niche which is even more undervalued than the wider Japanese mkt, offering thus investors a further margin of safety.

Sell-side coverage is often essential to attract investors and boost valuations but coverage can be expensive and time demanding and after 30 years of challenging markets many brokers have cut the number of companies under coverage.

As a result these companies trade a huge discount versus their peers, a discount which normally closes at initiation of broker coverage (or in the event of corporate action).

These are deep value opportunities: the 168 small and micro cap companies in our Orphan Companies portfolio trade an average PE of about 9x, a price to tangible book-value of about 0.6x and a net cash to market-cap ratio above 120%.

For further details see our Japanese Orphan Companies Project presentations.

For any questions email us on: info@nicheam.com

Follow us on LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/niche-am

Back Read More

The amount of negative press about ESG may be a sign that we are nearing the peak of the current backlash against ESG investing. Will the peak in negative sentiment be reached around Donald Trump’s possible re-election in November?

Everybody seems to be ranting against ESG these days. Some posit that the excessive number, complexity and sometimes vagueness and inconsistency of the UN’s SDGs make of these just a sort of humanity’s wish list, a mere list of desirables which is not accompanied by a realistic and effective strategy.

While they might have a point, it is just another sign of the current shift of the pendulum against ESG not only in media but also in politics and financial markets.

Investors who until very recently were happy to pay irrationally high multiples for ESG assets are now treating these as kryptonite even at ultra-low valuations.

Not us. We don’t see ESG investing as a transitory fad but as a structural and long-term mega-trend which is here to stay. All our investment portfolios are SDG-focussed, mostly as a way to minimise regulatory risk and ensure long-term profit growth. But also to maximise long-term investment performance.

Much of the recent scepticism around ESG performance is caused by the swinging fortunes of the energy sector. In fact, when controlling for sectoral effects (and also for investment style such as value and growth) it seems that ESG factors do continue to ensure outperformance, as nicely showed in the chart.

Back from vacation. The heat, while acceptable on the beach, is unbearable in town. The market is boring, weak, doomed. Good news is bad news. Bad news is, well, bad news. Good companies reporting bring a few percentage points of gain to the poor investor. Disappointment brings double digit losses. Why stick around? Why not sell and go back on beach?

Valuations?

There is a great deal of confusion in the market right now and many investors are still sceptical. They mention valuations, interest rates and economic slowdown as their primary concerns.

On valuations, we can say we have rarely in 25 years of tenure as fund managers experienced valuations that are so depressed. The indices apparently look expensive based on historical data. Those data do not take into consideration that today, in particular in the US, we have a significant amount of growth stocks in those indices. So, we would not rely on dumb averages. The stocks in the traditional sectors are, in many cases, very attractive. If we look at the risk premia, we also note that the actual ten-year interest rates cannot be considered a reference point due to its volatility. Common sense tells us that we should take an average of the last few years. Then, we have long term trends like energy transition and business onshoring that should support and energize the economy in the next few years. Last but not least, the inflation of the past three years has still to be fully reflected in the EPS.

If you take into account the previous elements, indexes composition, free risk, long term trends and laggard inflation effect on EPS, valuations are at their most attractive.

We think that once the economy presents its first signs of recession, unavoidable under the pressure of high interest rates, and the doomsayers start calling the stagflation myth, the traditional part of the market, the one that is now in value/deep-value territory, will gradually start to roar back, anticipating the inversion of the interest rates cycle. This is when retailers, consumer stocks, housing related stocks, leveraged companies, banks, etc, somewhat counterintuitively, will start to bounce back from shameful levels.

We are getting close to that moment. Today we think it is a perfect time to gradually accumulate deep value stocks. This part of the market includes thousands of quality names worldwide, very often far from the radar of investors who generally focus on about 5% of the total listed companies worldwide. It is now the time when “you can buy scores of decent companies at amazing prices”, quoting Warren Buffet.

What are we looking at these days?

The recent investment lull among the main telecom operators in North America has weakened the telecom equipment sector despite a global competitive outlook that has much improved. Here we find many companies we like.

We are also trying to time the end of the streaming war, tiptoeing into late comers, names like Paramount in the US, and RTL in Europe and others. These are companies with great content franchises. In one of our two multi thematic funds we also have a niche dedicated to publishers, a devasted sector where we see great revival potential. Bombarded by lots of fake news, democracies need to rely on serious journalism. The few survivors will thrive.

Renewables are again under pressure. What an opportunity! As we see Russia, the Middle East and China coordinating to support the oil price, pollution increasing and global warming producing the worth heatwaves to date, the market is again dumping the renewables players. The reason? There is a tug of war between the renewable energy supply chain and the utilities. The former wants significant price increases. The latter resists. It is normal. But the former will win in the end. We must take advantage of this phase. Buy the main players that present solid financial positions and clear undervaluation. We have an oversized position in Siemens Energy that is giving us some headaches, but we are happy to increase it on the way down. We are also adding to other renewable holdings, and we are introducing new ones in the US, Europe, Japan and South Korea.

In this phase of economic slowdown, we are also increasing on weakness stocks related to transportation, mostly in Europe where they are cheaper. We are also courting the timber sector, down with the cycle, but ready for a powerful rerating, forest owners in first place.

Companies in the sectors mentioned must be cautiously handled, some having significant financial and/or operational leverage and being now out of consensus. That’s why diversification is important. However, those and many other companies now present a great risk/benefit profile, the only metrics we use to appraise companies and build portfolios.

Our process

We define a strategy before investing. This strategy must clearly be flexible enough to be adjusted, but we tend not to be distracted by the news flow. We value the companies by what we see now, in terms of earnings potential (normalized) and assets held.

We do not speculate about long-term opportunities. If the companies are not deep value anymore, we take profit. Very rarely, we sell before our strategy plays out. Often, when all, according to the news flow, looks lost, something comes to the rescue. Before buying we want to see a huge discount, we are careful of debt, and we LOVE diversification (even if it has never been so unfashionable in the industry). Our funds proudly hold hundreds of stocks. This approach limits the impact of the black swans.

We buy gradually on the way down; we sell gradually on the way up. When we start to buy, normally the stock in the short term continues to go down. When we sell, the opposite happens. Sometimes we take partial profits before our target is reached if we see opportunities to further diversify our portfolios with stocks with a good risk/reward profile.

We are now very optimistic about the markets we follow. As mentioned above, there is such an abundance of quality stocks in the deep value camp. The market looks tired. The negatives apparently outnumber the positives. This makes the odds of a dramatic rebound in the many deep value stocks available even more likely.

As mentioned, the economy is also currently supported by robust geographical long-term trends. Europe and Japan could be coming out of stagnation. The China-driven world deflation pressures look to be gone. US economic drivers remain robust. Korea, Indonesia and a number of other countries can be seen as manufacturing alternative to China.

Central banks are weakening the economy to break inflation’s back. However, central banks can be very fast to reflate the economy if it weakens too much. Again, once inflation is tamed (and the market always tries to anticipate this) we expect a violent rerating of this part of the market.

We don’t know what will happen in the next few months but, again, we think the downside on our universe is limited, the upside huge. Here we see an opportunity. Be patient. Quit the screen, buy a few books, travel, relax. It is incredible how laziness can be rewarding in stock markets…

Read More

What is Siemens Energy?

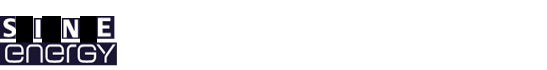

Siemens Energy is a beautiful multinational listed in Germany. It is a spin-off from Siemens in 2020. It contains two macro-businesses. The first brings together activities related to the energy grid, turbines and hydrogen. The second is a leader in the production and operation of windmills for wind energy production. We are in the era of the energy transition, where trillions of dollars will be spent to reduce poisonous CO2 emissions by investing in renewables and modernising the energy grid and infrastructure. Today, the world has about 8 Terawatts of electricity generation capacity, which is set to grow significantly with the development of electric mobility. To meet the NET ZERO EMISSION scenario to be reached in 2050, the share of electricity generation from renewables and other low-emission sources will have to increase from 37% to 73% by 2030 (see chart below).

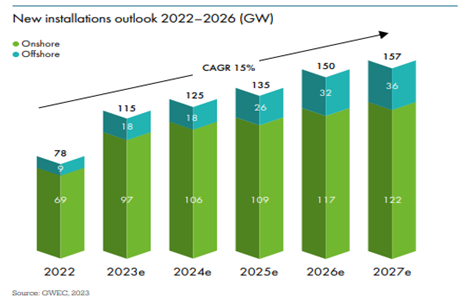

It took 33 years to reach one Terawatt (1000 Giga) of wind power capacity. According to GWEC (Global Wind Energy Council – GWEC-2023_interactive.pdf) this capacity will be doubled in the next 7 years (below is a histogram showing the expected growth in wind power capacity). Apparently, there is no better place to be invested to benefit from Siemens Energy’s energy transition trend. Apparently.

What happened?

As mentioned earlier, the company can be divided into two major divisions, one instrumental in the efficiency enhancement of existing power generation and transmission facilities, and the other focused on the production, installation and operation of the windmills that we see more and more around us when we leave our cities. The first division is emerging from a twenty-year torpor characterised by over-competition and under-investment. This resurgence is due to industry consolidation, limited Chinese competition in such a strategic sector, and the political will to drastically limit greenhouse gas emissions, which implies huge investments for the next decade.

By contrast, the second division, whose name is Siemens Gamesa, is going through a difficult phase due to its complex and relatively new nature. The construction of these wind farms consisting of hundreds of huge mills is an exercise of cyclopean proportions. To give the reader a point of reference, an offshore (shallow waters) wind farm with a capacity of one gigawatt (i.e. 1000 megawatts, the power needed to keep 100 million LED lights switched on or to supply energy to more than 500,000 households) costs around EUR 3 billion to build and around EUR 100 million per year to operate. The development of such projects extends over several years, from a minimum of 2 years up to 7 years. The organisation required is therefore very complex, not far from that needed to build a nuclear power plant and much greater than that needed to build a large dam. For the same capacity, the use of steel is 15 times higher than for a gas-fired power station. The order book for these orders extends over several years, with contracts, however, only marginally considering changes in the cost of materials. In addition, there is no compensation for site interruptions due to exceptional causes. The Pandemic and Ukrainian invasion have therefore created significant losses on these multi-year contracts. And this is only the oldest part of the story that took the share price from over EUR 30 per share to less than EUR 11 about two years ago. As is always the case, the industry then revised its price list significantly and managed to agree more favourable terms with customers that would guarantee them good future profitability. This allowed the stock to recover from EUR 11 per share to EUR 24 per share. Now comes the best part.

In May 2023, the company issued a statement in which it revised upwards its profit estimates for 2023 (the company’s statutory year ends at the end of September). The reasons lie in the first division, which sees demand and prices rising sharply. The release also mentions the second division, Siemens Gamesa, saying that progress is slower than hoped and will only be seen towards the end of the year. So, we have a division in top form and confirmation that, although slower than expected, Siemens Gamesa is recovering. Fifteen days later these elements are confirmed at the JPM conference in London (qui il link alla presentazione). In this context, even those who had exited the stock due to the disappointments associated with Siemens Gamesa gradually re-entered, pushing the share to EUR 24, a new high for the period. At that valuation, the company was still very attractive even for those of us who are ‘deep value’, i.e. we invest for what we see today, not what might be in the future. In fact, at that price, the company had a capitalisation of around EUR 19 billion. Valuing the first division at a humble earnings multiple of 11x and adding the Indian JV at market values we arrive at about 17 billion euros. The implied valuation for Siemens Gamesa was thus 2 billion, or less than 0.2X EV/Sales, one-sixth of what the company recently paid to take it off the market (4 billion for one-third of the company, so 12 billion euros) and one-eighth of the EV/Sales multiple of rival Vestas (EV/Sales 1.6X). Assuming stable sales and a return to an EBIT margin of 10% Siemens Gamesa is conservatively worth at least €12 billion (1.2X EV/Sales, 11X EV/EBIT), thus €10 billion more than it was valued at when it was worth €24, or €36 per share. Clearly the EBIT margin of 10% was not around the corner, but it was an achievable result.

On 21 June, the company came out with an explosive statement: the Siemens Gamesa division found new component and/or design problems on about 1/3 of the installed base. This will result in over 1 billion costs spread over 5 years and delay the turnaround. The company reaffirms the recently released sales and profitability targets on the first division. It withdraws the targets as a group, as it cannot yet quantify the unexpected costs on Siemens Gamesa. The share price will lose about 40 per cent of its capitalisation, EUR 8 billion, over the next two days. A large part of this fall is due to the fact that investors who entered after the recent increase in earnings estimates have exited, regardless of price, and that a number of investors who were already there have reduced their positions or not increased them by virtue of the confusion that seems to reign within the company, where problems of an extremely significant magnitude emerge from one day to the next, with top management seemingly completely uninvolved in the company’s performance.

Kitchen sinking?

Kitchen Sinking refers in finance to the attitude of providing more negative information than one already has about the company one is managing. While this immediately implies a negative effect, it also ‘skews’ expectations, improving the perception of future data. This is often done by new managers in order to take credit for future improvement. With the acquisition of the 33 per cent of Siemens Gamesa not held by Siemens Energy, the old management of this division was replaced and the leavers were blamed for much of the responsibility for the company’s years of difficulties. It is possible that the management made this unexpected decision in order to set the tone and exaggeratedly lower expectations.

DEJA VU’?

It was the year 2006 and we were investing in EADS, the company that many years later would be renamed AIRBUS. The company had many points in common with today’s Siemens Energy: 1) engaged in the capital equipment sector with multi-year orders and sensitive technology 2) the business growth prospects were exceptionally favourable 3) the company had two divisions, one producing fat profits (the Defence division) and one in difficulty (the Civil Aircraft division) 3) the division in difficulty complained of significant technical and internal communication problems 4) the company operated in an oligopoly regime with very high barriers to entry 5) the company was defended against Chinese competition 6) the company was politically significant.

It took EADS a few years to get back on its feet, but then, gradually, the rerating came. At the end of 2009, Airbus was worth about €12 billion (as Siemens Energy is today) with €42 billion in sales (Siemens Energy’s sales expected to be €34 billion next year) and a loss of about €800 million resulting from over-costs related to the A380 and A350 projects (about €1 billion in losses related to exceptional components for Siemens Gamesa). In ten years, the Airbus share has increased tenfold. Today Airbus is one of the most heavily weighted European stocks in portfolios, perceived as high quality and certainly benefiting from Boeing’s weakness and the focus in Europe on the defence sector. However, at 16x EV/Ebit we believe it does not present a sufficiently attractive risk/benefit profile given the many risks in the sector, unlike Siemens Energy.

Conclusion

Today Siemens Energy represents the classic dead dog or ‘show me’ company, i.e. a company that will have to radically surprise us in order to gradually catch up. It will probably take time and the terrain in any case remains slippery and much can still go wrong. However, the risk/benefit profile, the metric against which we assess every investment, is outstanding. The company has no debt, has a division that is doing very well with high operating leverage, and we believe that rarely has it been possible to buy a jewel like Siemens Gamesa at these valuations. By giving a valuation of 17 billion to the first division today you can buy Siemens Gamesa at a negative value of 6 billion!!! We therefore used the recent weakness to increase our positions on this company.

Nuova nicchia sul fondo Pharus Asian Value Niche

Market context

Opportunistically we seize this phase of market confusion to add a new niche. The market continues to be worried about central banks raising rates. Central banks are worried about inflation. Persistent inflation is in the current environment both inevitable and positive. Inevitable because the deflationary effect that China has exerted for two decades, sending much of the world into stagnation, is gradually disappearing. Positive because it reflects huge investments directed towards the energy transition and the rebuilding of a more reliable supply chain. It will bring down public and private debts. It will restore some of the social equity lost in recent years. It will lay the groundwork for a rise in the value component of the market that, when it comes, will be formidable, not unlike what we saw in similar situations in 1950 and 1982. Rising rates will not stop these investments but will inevitably bring problems to areas that have adapted to a very low-rate environment. We are witnessing and will witness a general clean-up of speculation that is still strong. The victims, as always, will be those who have taken the most risk; hence, have benefited from a lot of debt or excess liquidity to seek returns in speculative investments. While much of the Private Equity and Private Debt around is of quality, there is a not insignificant part of it that will go bad. It will be understood that returns of 15%/25% per year are not always the result of shining minds, but rather of the most trivial leverage. It is easily understood that a number of these gentlemen have been exchanging assets for years in order to make the famous exits. Other areas also need to be checked, in particular that sympathetically termed ‘real assets’, a definition that slyly tends to create an inappropriate sense of comfort in the end investor. We, as free-range and unrefined individuals, keep an eye on bitcoin, which has recovered well this year. Indeed, we are convinced that the beginning of the fall in rates and the subsequent historic rally in equity (value) will follow the final collapse of cryptocurrencies, the summa maxima of a historical phase defined by unbridled globalization, global stagnation, a riot of inequality and nationalism, negative rates and speculation.

Globalization by Vsevolod Slavutych

“Deglob” Niche

Many times, we have discussed deglobalization. If globalization has been the theme of the past 20 years and having understood, it and followed it in investment choices would have helped a lot. In the next 10 years deglobalization, we believe, will have equally profound repercussions. Many sectors will be affected and that could completely overhaul, positively or negatively, their business structure. We therefore create a portfolio within the Pharus Asia Value Niche fund including companies that will benefit from these changes. The sectors are the most diverse, from companies related to the semiconductor ecosystem, ingredients for pharmaceuticals, construction, metal refining, steel, communications infrastructure, renewables and many others. Siemens Energy, which we mentioned above, is clearly one of the beneficiaries of this trend and one of the stocks in this portfolio (here is an interesting article on the subject NZIA: act now or Europe’s wind turbines will be made in China | WindEurope ).

As always, there will have to be three characteristics. In addition to being able to benefit from deglobalization, companies will have to have ‘deep value’ valuations, in line with our approach, and they will have to be sustainable in the sense that they will have to position themselves on a path of gradual improvement with respect to social, environmental and governance factors. Through direct interaction with companies, we are committed to ensuring and documenting this. The new Niche starts with a weight of 1.5 per cent and has a maximum weight of 2.5 per cent of the portfolio’s NAV. Initially it consists of 15 securities which we will gradually increase to 25.