SINE Energy

What is Siemens Energy?

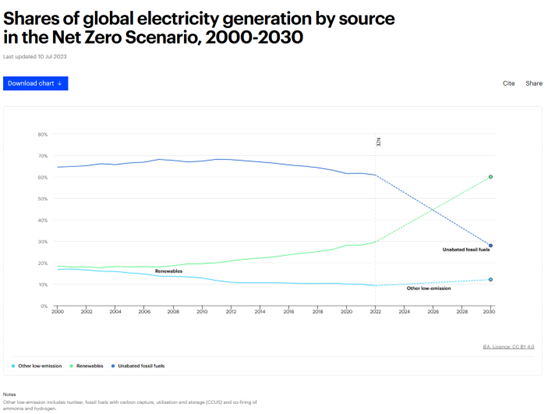

Siemens Energy is a beautiful multinational listed in Germany. It is a spin-off from Siemens in 2020. It contains two macro-businesses. The first brings together activities related to the energy grid, turbines and hydrogen. The second is a leader in the production and operation of windmills for wind energy production. We are in the era of the energy transition, where trillions of dollars will be spent to reduce poisonous CO2 emissions by investing in renewables and modernising the energy grid and infrastructure. Today, the world has about 8 Terawatts of electricity generation capacity, which is set to grow significantly with the development of electric mobility. To meet the NET ZERO EMISSION scenario to be reached in 2050, the share of electricity generation from renewables and other low-emission sources will have to increase from 37% to 73% by 2030 (see chart below).

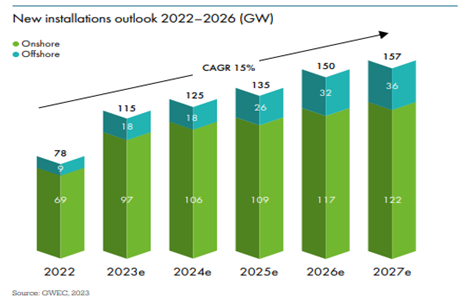

It took 33 years to reach one Terawatt (1000 Giga) of wind power capacity. According to GWEC (Global Wind Energy Council – GWEC-2023_interactive.pdf) this capacity will be doubled in the next 7 years (below is a histogram showing the expected growth in wind power capacity). Apparently, there is no better place to be invested to benefit from Siemens Energy’s energy transition trend. Apparently.

What happened?

As mentioned earlier, the company can be divided into two major divisions, one instrumental in the efficiency enhancement of existing power generation and transmission facilities, and the other focused on the production, installation and operation of the windmills that we see more and more around us when we leave our cities. The first division is emerging from a twenty-year torpor characterised by over-competition and under-investment. This resurgence is due to industry consolidation, limited Chinese competition in such a strategic sector, and the political will to drastically limit greenhouse gas emissions, which implies huge investments for the next decade.

By contrast, the second division, whose name is Siemens Gamesa, is going through a difficult phase due to its complex and relatively new nature. The construction of these wind farms consisting of hundreds of huge mills is an exercise of cyclopean proportions. To give the reader a point of reference, an offshore (shallow waters) wind farm with a capacity of one gigawatt (i.e. 1000 megawatts, the power needed to keep 100 million LED lights switched on or to supply energy to more than 500,000 households) costs around EUR 3 billion to build and around EUR 100 million per year to operate. The development of such projects extends over several years, from a minimum of 2 years up to 7 years. The organisation required is therefore very complex, not far from that needed to build a nuclear power plant and much greater than that needed to build a large dam. For the same capacity, the use of steel is 15 times higher than for a gas-fired power station. The order book for these orders extends over several years, with contracts, however, only marginally considering changes in the cost of materials. In addition, there is no compensation for site interruptions due to exceptional causes. The Pandemic and Ukrainian invasion have therefore created significant losses on these multi-year contracts. And this is only the oldest part of the story that took the share price from over EUR 30 per share to less than EUR 11 about two years ago. As is always the case, the industry then revised its price list significantly and managed to agree more favourable terms with customers that would guarantee them good future profitability. This allowed the stock to recover from EUR 11 per share to EUR 24 per share. Now comes the best part.

In May 2023, the company issued a statement in which it revised upwards its profit estimates for 2023 (the company’s statutory year ends at the end of September). The reasons lie in the first division, which sees demand and prices rising sharply. The release also mentions the second division, Siemens Gamesa, saying that progress is slower than hoped and will only be seen towards the end of the year. So, we have a division in top form and confirmation that, although slower than expected, Siemens Gamesa is recovering. Fifteen days later these elements are confirmed at the JPM conference in London (qui il link alla presentazione). In this context, even those who had exited the stock due to the disappointments associated with Siemens Gamesa gradually re-entered, pushing the share to EUR 24, a new high for the period. At that valuation, the company was still very attractive even for those of us who are ‘deep value’, i.e. we invest for what we see today, not what might be in the future. In fact, at that price, the company had a capitalisation of around EUR 19 billion. Valuing the first division at a humble earnings multiple of 11x and adding the Indian JV at market values we arrive at about 17 billion euros. The implied valuation for Siemens Gamesa was thus 2 billion, or less than 0.2X EV/Sales, one-sixth of what the company recently paid to take it off the market (4 billion for one-third of the company, so 12 billion euros) and one-eighth of the EV/Sales multiple of rival Vestas (EV/Sales 1.6X). Assuming stable sales and a return to an EBIT margin of 10% Siemens Gamesa is conservatively worth at least €12 billion (1.2X EV/Sales, 11X EV/EBIT), thus €10 billion more than it was valued at when it was worth €24, or €36 per share. Clearly the EBIT margin of 10% was not around the corner, but it was an achievable result.

On 21 June, the company came out with an explosive statement: the Siemens Gamesa division found new component and/or design problems on about 1/3 of the installed base. This will result in over 1 billion costs spread over 5 years and delay the turnaround. The company reaffirms the recently released sales and profitability targets on the first division. It withdraws the targets as a group, as it cannot yet quantify the unexpected costs on Siemens Gamesa. The share price will lose about 40 per cent of its capitalisation, EUR 8 billion, over the next two days. A large part of this fall is due to the fact that investors who entered after the recent increase in earnings estimates have exited, regardless of price, and that a number of investors who were already there have reduced their positions or not increased them by virtue of the confusion that seems to reign within the company, where problems of an extremely significant magnitude emerge from one day to the next, with top management seemingly completely uninvolved in the company’s performance.

Kitchen sinking?

Kitchen Sinking refers in finance to the attitude of providing more negative information than one already has about the company one is managing. While this immediately implies a negative effect, it also ‘skews’ expectations, improving the perception of future data. This is often done by new managers in order to take credit for future improvement. With the acquisition of the 33 per cent of Siemens Gamesa not held by Siemens Energy, the old management of this division was replaced and the leavers were blamed for much of the responsibility for the company’s years of difficulties. It is possible that the management made this unexpected decision in order to set the tone and exaggeratedly lower expectations.

DEJA VU’?

It was the year 2006 and we were investing in EADS, the company that many years later would be renamed AIRBUS. The company had many points in common with today’s Siemens Energy: 1) engaged in the capital equipment sector with multi-year orders and sensitive technology 2) the business growth prospects were exceptionally favourable 3) the company had two divisions, one producing fat profits (the Defence division) and one in difficulty (the Civil Aircraft division) 3) the division in difficulty complained of significant technical and internal communication problems 4) the company operated in an oligopoly regime with very high barriers to entry 5) the company was defended against Chinese competition 6) the company was politically significant.

It took EADS a few years to get back on its feet, but then, gradually, the rerating came. At the end of 2009, Airbus was worth about €12 billion (as Siemens Energy is today) with €42 billion in sales (Siemens Energy’s sales expected to be €34 billion next year) and a loss of about €800 million resulting from over-costs related to the A380 and A350 projects (about €1 billion in losses related to exceptional components for Siemens Gamesa). In ten years, the Airbus share has increased tenfold. Today Airbus is one of the most heavily weighted European stocks in portfolios, perceived as high quality and certainly benefiting from Boeing’s weakness and the focus in Europe on the defence sector. However, at 16x EV/Ebit we believe it does not present a sufficiently attractive risk/benefit profile given the many risks in the sector, unlike Siemens Energy.

Conclusion

Today Siemens Energy represents the classic dead dog or ‘show me’ company, i.e. a company that will have to radically surprise us in order to gradually catch up. It will probably take time and the terrain in any case remains slippery and much can still go wrong. However, the risk/benefit profile, the metric against which we assess every investment, is outstanding. The company has no debt, has a division that is doing very well with high operating leverage, and we believe that rarely has it been possible to buy a jewel like Siemens Gamesa at these valuations. By giving a valuation of 17 billion to the first division today you can buy Siemens Gamesa at a negative value of 6 billion!!! We therefore used the recent weakness to increase our positions on this company.

Nuova nicchia sul fondo Pharus Asian Value Niche

Market context

Opportunistically we seize this phase of market confusion to add a new niche. The market continues to be worried about central banks raising rates. Central banks are worried about inflation. Persistent inflation is in the current environment both inevitable and positive. Inevitable because the deflationary effect that China has exerted for two decades, sending much of the world into stagnation, is gradually disappearing. Positive because it reflects huge investments directed towards the energy transition and the rebuilding of a more reliable supply chain. It will bring down public and private debts. It will restore some of the social equity lost in recent years. It will lay the groundwork for a rise in the value component of the market that, when it comes, will be formidable, not unlike what we saw in similar situations in 1950 and 1982. Rising rates will not stop these investments but will inevitably bring problems to areas that have adapted to a very low-rate environment. We are witnessing and will witness a general clean-up of speculation that is still strong. The victims, as always, will be those who have taken the most risk; hence, have benefited from a lot of debt or excess liquidity to seek returns in speculative investments. While much of the Private Equity and Private Debt around is of quality, there is a not insignificant part of it that will go bad. It will be understood that returns of 15%/25% per year are not always the result of shining minds, but rather of the most trivial leverage. It is easily understood that a number of these gentlemen have been exchanging assets for years in order to make the famous exits. Other areas also need to be checked, in particular that sympathetically termed ‘real assets’, a definition that slyly tends to create an inappropriate sense of comfort in the end investor. We, as free-range and unrefined individuals, keep an eye on bitcoin, which has recovered well this year. Indeed, we are convinced that the beginning of the fall in rates and the subsequent historic rally in equity (value) will follow the final collapse of cryptocurrencies, the summa maxima of a historical phase defined by unbridled globalization, global stagnation, a riot of inequality and nationalism, negative rates and speculation.

Globalization by Vsevolod Slavutych

“Deglob” Niche

Many times, we have discussed deglobalization. If globalization has been the theme of the past 20 years and having understood, it and followed it in investment choices would have helped a lot. In the next 10 years deglobalization, we believe, will have equally profound repercussions. Many sectors will be affected and that could completely overhaul, positively or negatively, their business structure. We therefore create a portfolio within the Pharus Asia Value Niche fund including companies that will benefit from these changes. The sectors are the most diverse, from companies related to the semiconductor ecosystem, ingredients for pharmaceuticals, construction, metal refining, steel, communications infrastructure, renewables and many others. Siemens Energy, which we mentioned above, is clearly one of the beneficiaries of this trend and one of the stocks in this portfolio (here is an interesting article on the subject NZIA: act now or Europe’s wind turbines will be made in China | WindEurope ).

As always, there will have to be three characteristics. In addition to being able to benefit from deglobalization, companies will have to have ‘deep value’ valuations, in line with our approach, and they will have to be sustainable in the sense that they will have to position themselves on a path of gradual improvement with respect to social, environmental and governance factors. Through direct interaction with companies, we are committed to ensuring and documenting this. The new Niche starts with a weight of 1.5 per cent and has a maximum weight of 2.5 per cent of the portfolio’s NAV. Initially it consists of 15 securities which we will gradually increase to 25.