The curious case of Japanese conglomerates

Download Pdf

The curious case of Japanese conglomerates (1)

Katakura Industries is a funny small cap company. It was founded in 1873 and is based in the special district of Chuo, within the Tokyo metropolitan area. The company is undoubtedly diversified. It is one of the leaders in the vitamin market in Japan and is also active in the cardiovascular sector with three drugs it has developed (Frandol, Frandol tape and Bisono).  The company is active in the textile sector, where it produces linens, particularly in silk, whose brand is popular in Japan. It is also active in the production and sale of the water-soluble fibre Solvon and the heat-resistant alumina-based fibre NITIVY. The company manufactures industrial liquid purification machinery and fire trucks. It breeds and sells bees and produces and distributes honey. It operates a chain of nurseries. It offers cleaning and maintenance for apartment buildings and industrial areas. It owns a few large shopping centres and is active in the buying and selling of real estate of all kinds. Sounds crazy? Well this is normal in Japan! Whether large or small, listed companies are almost all conglomerates operating in a wide variety of fields. This clearly makes it difficult to analyse the company using the quant methodologies that the market usually uses. Even those who look at the fundamentals are often in trouble because 80% of listed companies in Japan are not covered by analysts and another 8% are undercover. This explains why almost half of the companies in Japan trade below tangible equity. And you understand more about the logic behind our Orphan Companies Niche, which seeks to identify the most promising and undervalued companies in this large and beautiful universe. Like Benjamin Button was abandoned by his mother, Japanese companies are abandoned by investors. Appearance matters. The Orphan Companies represent the cases where the undervaluation of Japanese companies reaches its peak.

The company is active in the textile sector, where it produces linens, particularly in silk, whose brand is popular in Japan. It is also active in the production and sale of the water-soluble fibre Solvon and the heat-resistant alumina-based fibre NITIVY. The company manufactures industrial liquid purification machinery and fire trucks. It breeds and sells bees and produces and distributes honey. It operates a chain of nurseries. It offers cleaning and maintenance for apartment buildings and industrial areas. It owns a few large shopping centres and is active in the buying and selling of real estate of all kinds. Sounds crazy? Well this is normal in Japan! Whether large or small, listed companies are almost all conglomerates operating in a wide variety of fields. This clearly makes it difficult to analyse the company using the quant methodologies that the market usually uses. Even those who look at the fundamentals are often in trouble because 80% of listed companies in Japan are not covered by analysts and another 8% are undercover. This explains why almost half of the companies in Japan trade below tangible equity. And you understand more about the logic behind our Orphan Companies Niche, which seeks to identify the most promising and undervalued companies in this large and beautiful universe. Like Benjamin Button was abandoned by his mother, Japanese companies are abandoned by investors. Appearance matters. The Orphan Companies represent the cases where the undervaluation of Japanese companies reaches its peak.

Katakura Industries is one of the 100 or so companies we hold in the Orphan Companies Niche (a Niche that occupies 10% of the Asian Niches fund), a group of companies with which we methodically talk and engage. Katakura Industries has been the subject of a takeover bid in recent days. The premium is almost 70% over the price at which the company was trading before the rumours started to leak out. At the offered price, the company is worth 12x earnings, 1.1x tangible equity and has net cash of about 50% of its capitalisation. We’ll leave it to the reader to do the math on what it was worth before the offer….

The curious case of Japanese conglomerates (2)

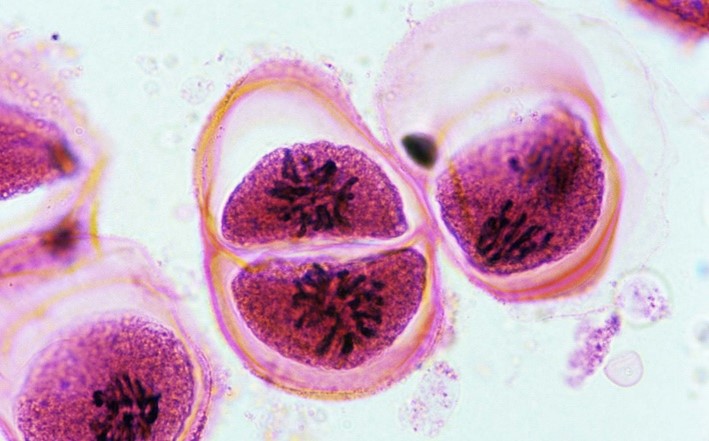

In 2017/18 in Japan, the METI (Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry) introduced a tax reform aimed at protecting shareholders of conglomerate companies from tax burdens in the event of corporate demergers. The aim was to stimulate corporate simplification. As in meiosis, a process that divides cells into cells with a simpler genetic make-up, thus biologically suitable for efficient reproduction, the process of corporate splitting involves the creation of simpler corporate entities, suitable for engaging in aggregation operations, with the aim of improving the likelihood that the corporation will survive and develop.

The transformation of conglomerates into pure companies was supposed to lead to market rerating and a wave of M&A transactions. In fact, so far this transformation process does not seem to have really started. However, together with the tax reform, there are a series of other factors that are pushing in this direction: 1) the new code of corporate conduct (which focuses on independent directors); 2) the moral suasion of the government and the BOJ to reduce cross-shareholding between companies (even today, about 1/3 of the shares of Japanese listed companies are held by cross-shareholders who tend to maintain the status quo); 3) the increase of activist Western shareholders; 4) the less interference of the government and the courts in corporate action cases.

Toshiba announced a few days ago that it is ready to split into three parts: 1) a division with office machines and with the aim of listing Kioxia, the subsidiary active in storage that should be worth half of the current capitalisation of Toshiba; 2) the Device division (which will contain mostly hard disks and semiconductors); and 3) the Infrastructure division, active in many sectors that now have great growth prospects (including nuclear power, which makes it strategically important for the country and not acquirable by foreign subjects).

In the pages of the FT, Leo Lewis, a journalist who is an expert on Japan, expresses his hesitations that Toshiba’s split could represent the beginning of a new cycle (click here to view it). He also mentions Panasonic and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries as clear candidates for a split.  We can’t help but understand the journalist’s frustration and scepticism after years of waiting for something to change in Japan. However, we are more positive.

We can’t help but understand the journalist’s frustration and scepticism after years of waiting for something to change in Japan. However, we are more positive.

These changes are long and never seem to come, but when they do, they are powerful. In addition to Toshiba, we read other signs. Panasonic, mentioned in the FT, has reorganised the company into new divisions that will be truly separate. So the profits of one will no longer be used to cover the losses of another. The company hinted that the battery division might be listed. Shinsei Bank, a major Japanese bank, suffered a hostile take-over by another Japanese institution, which was unthinkable until yesterday. In addition, this will be the year when Japan will have the largest number of M&A deals ever. All over the world we see a trend towards simplifying corporate structures. Giants GE and J&J announced this week that they are splitting into 3 and 2 new listed companies respectively. In Japan, the land of conglomerates, this kind of trend can create a telluric movement, with great benefits for shareholders.

Food and robotics

The evolution of supermarkets has come a long way. Once upon a time, you went into a grocer’s, had a chat and asked the grocer what you needed. Today, this is only done in a few villages. There was a human contact that no longer exists.

However, the change goes back a long way.

In 1917 in Memphis, Tennessee, a new format for supermarkets was introduced. Customers were finally free to take what they wanted from the shelves and bring it to the cashier who put it in the bags, counted it and gave change. It was a revolution. Productivity exploded, as did the satisfaction of a large proportion of customers. However, there were many who, as always happens, found the situation too impersonal or uncomfortable. As always, some people take longer to adapt.

In 1967 the queues became shorter. In fact, Kruger developed the first scanner and started putting a readable label on each product. A few years later, the first UPC (Uniform Product Code) was developed by IBM and gradually adopted by the entire food retail sector, in the USA and abroad. As well as reducing queues, this greatly improved the efficiency of logistics.

A few years later, in 1984, David R Humble invented the first automatic checkout. They began to be used in the 1990s and have exploded in the last fifteen years. It’s hard not to see some in every supermarket. Their spread stems from the need for supermarkets to be more competitive and profitable. According to a recent OECD study (click here to view it), 1/3 of the workforce in this sector will disappear in the next few years due to automation.

On automated checkouts, consumer feedback is mixed. In fact, if you have a bottle of wine you have to look for the attendant to show your ID. Some codes don’t go through right away and the process gets stuck. Other times, it is difficult to get the product in front of the scanner (case of water). Finally, in other circumstances, the blockage results from factors that are not understood by the frustrated buyer, who is stuck for several minutes before being released with his litre of milk (waiting in line in front of the cashier is less frustrating as the process is at least clear to us).

The first machines had no voice. Then came those with electronic voices and rude manners. Now the voice is human and the manners polite. Often much more courteous than the cashier who barely says hello and no longer puts the shopping in the bags. It is not clear whether this is intentional, but it certainly acts as an incentive to use the automatic checkouts…

Today, in addition to focusing on improving the automatic checkout, we are moving into new frontiers that will inevitably encounter other problems that, in time, will, again, be solved. In 2016, with great fanfare, Amazon launched the Amazon GO format (here is a video presentation). In these shops, you register once and then go in, get what you need and leave. The receipt arrives directly on your phone and the bill is debited from your card. A series of sensors detect what the customer has taken without the need for annoying queues. This year the format was closed. How come? While it looked easy on paper, just like automatic checkouts, there are a number of complications that risk spoiling the experience. And it takes time. Technology and connectivity have to improve. It has to be really convenient for the customer and, above all, they have to get used to it. While Amazon Go closed, Tesco launched the same format in London and it seems to be working. On the other side of the world, in Korea, E-Mart, the country’s largest chain, launched its first unmanned shop in September. In Korea, 5G is already up and running (although far from being what it will be in the next few years in terms of speed and latency) and the appetite for the technology is high. The shops are structured with technology from a group company, Shinsegae Information&Comunication, 35% owned by E-Mart. Here is a video on the company’s technology, which is reminiscent, in a coldly more Korean way, of Amazon. For those of us who think that this is the future, whether we like it or not, it makes sense to take a look at this company which, in addition to being a major player in the sector, can boast of having a giant shareholder/client behind it that can give it some visibility on orders. Since the COVID lows recorded in 2020, the company has risen 150%, but remains at 8.5x earnings, 1.4x tangible equity and with 1/3 of capitalisation in net cash. Korean market magic…

Back